“One morning in Rome I ran down the steps of the Grand Hotel as fast as I could, armed with a strange box tied round with string and sealed with lead. This box contained one of my paintings. In the foyer, René Clair was sitting, reading the paper. He lifted his eyes, those eyes that are always sceptical, with dark circles under them caused, as everyone knows, by the incurable wound of Cartesian deception. He said to me: ʻWhere are you off to in such a hurry, at this time of day, and with all those strings?ʼ I answered curtly and with maximum dignity: ʻI’m going to see the Pope and then I’m coming back. Wait for me here”.

Salvador Dalí

.

With these words, Salvador Dalí recounted his extraordinary meeting with Pope Pius XII, which took place on November 23rd, 1949. An episode that might seem absurd or surreal, but is in fact real, documented by a Vatican communiqué issued that very day.

Among the many reasons for the visit, the most important for Dalí was his desire to obtain the Pope’s permission to marry Gala in the Church, a complicated request, as Gala had already been married to the French poet Paul Éluard, who was still alive.

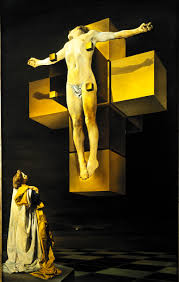

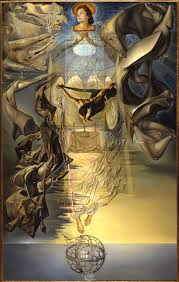

To support his case, Dalí decided to present the Pope with an emblematic work: The Madonna of Port Lligat, depicting Gala as the Virgin Mary. This painting marked the beginning of the so-called Nuclear Mysticism phase, a fundamental turning point in the Catalan artist’s spiritual and artistic journey.

At a time when the Catholic world and all of humanity mourn the passing of Pope Francis, the artist of dreams and visions invites us to reflect on the spiritual dimension of art and that search for God that runs, like an invisible thread, through his vast artistic production.

Dalí was never a man of half measures. While interest in the Sacred is common among many artists, for him, religion was a realm to be explored inwardly — a space for mystical inquiry suspended between faith and science, myth and theology. This search culminated in the “nuclear mystic” period, during which he created some of his most significant masterpieces.

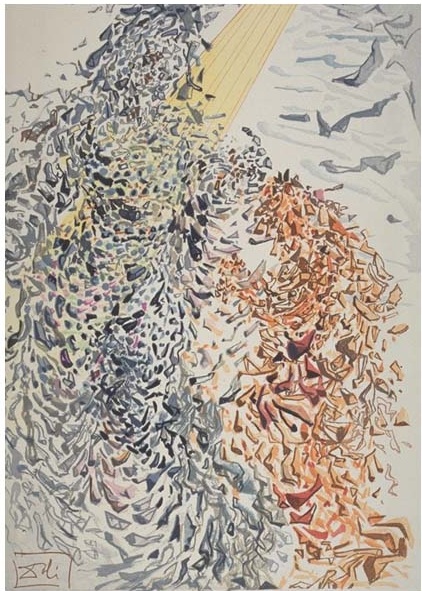

Fascinated by the restlessness and contradictions of the Sacred, Dalí illustrated religious works such as the Bible (a monumental project composed of 105 graphics, to which he dedicated six years) and the Divine Comedy. Gala, his muse and wife, frequently appears in these images, depicted as the Madonna, as an angel, or as a divine figure. In her, Dalí saw the embodiment of the sacred feminine.

After the Second World War and the explosion of the atomic bomb, Dalí was deeply shaken. The revelation of the invisible force contained in matter led him to unite modern physics with theology. Thus was born Nuclear Mysticism, in which molecular biology, particle physics, and mathematics intertwine with dogmas and mystical visions. Dalí dreamed, for example, of seeing an atom transform into Christ, the center of the Universe.

In Dalí’s thinking, the Madonna does not ascend to Heaven by divine intervention, but through an opposite force: that of antiprotons. A vision that merges mysticism and quantum mechanics, faith and particle physics.

Dalí’s art, from painting to sculpture, is crossed by a vertical tension that points to the sky, the same sky his mustache aimed toward: “sharp, imperialist and pointed toward the sky, like vertical mysticism”, as the Master of Surrealism declared himself.

Dalí’s relationship with religion was one of constant evolution and inquiry. Through Surrealism, Dalí examined the Divine as no other artist of the 20th century did. For Dalí, Gala was the Madonna, the Madonna was the atom, the atom was Christ, and Christ was the center of the Universe.

He wrote after reading Nietzsche: “The only difference between a madman and me is that I am not mad.” In truth, Salvador Dalí was not mad: he was a mystic. And today, more than ever, in the silence following the passing of Pope Francis, the Pope of mercy, Dalí’s mystical and spiritual Surrealism echoes the great question: where is Heaven?

Raised in a divided household, his father a staunch atheist, his mother a devout Catholic, Dalí maintained a tumultuous relationship with Faith during his rebellious adolescence and youth, only to return to religious exploration in adulthood, never truly able to abandon the formative Faith of his childhood.

Dalí learned from the atheist books in his father’s library that “God does not exist”. His first teacher, Don Esteban Trayter, spent an entire year telling Dalí that God did not exist, claiming “that religion was a woman’s business.”

It was Nietzsche who opened the door to Faith for Dalí, along with his mother’s example, sparking the artist’s first mystical questions and doubts, which would reach their full expression in 1951 with the publication of his Mystic Manifesto. “Nietzsche awoke in me the idea of God”, wrote Dalí in his autobiography The Secret Life of Salvador Dalí.

A perfect example of Dalinian spirituality is the sculpture “Saint George and the Dragon”. Here, Dalí reinterprets a classic Christian tale through a surrealist lens, exploring the duality between life and death, good and evil.

The composition is rich with symbols: the horse, impassive and brave, seems to draw strength from the surrounding flames, transmitting energy to the rider. It does not flee, but faces the darkness. The rider, Saint George, receives this strength and defeats the dragon, a symbol of human temptations and obsessions.

Interesting is the metamorphosis of the dragon’s tongue into a crutch. For Dalí, the crutch is “the symbol of death and the symbol of resurrection”, of collapse and rebirth. Only through the symbolic death of the dragon, of fears, impulses, and inner shadows, can one access a new life, a new balance.

Today, as the world gathers to remember Pope Francis, the Pope of Mercy, Salvador Dalí’s art offers us the chance to view Faith through art. For Dalí, Heaven is not merely a spiritual dimension: it is a mystical explosion of atoms, symbols, and truths.

And perhaps, as his works suggest, it is precisely there, on that subtle boundary between Faith and science, madness and genius, that the true nature of the Divine lies hidden.

“Heaven is to be found, neither above nor below, neither to the right nor to the left, heaven is to be found exactly in the center of the bosom of the man who has Faith!”

Salvador Dalí