“My brother and I resembled each other like two drops of water, but we had different reflections”.

Salvador Dalí

.

October 12th marked the date of birth, in 1901, of the first son of Salvador Dalí Cusí and Felipa Domènech Ferrés, a child also christened Salvador Dalí, but destined to die prematurely from meningitis.

That boy is the keystone, the archetypal phantom whose shadow was cast over the cradle of the second Salvador Dalí, the Catalan genius born less than nine months after his death, on May 11th, 1904.

His brief existence was not a mere memory, but the psychological wound that shaped the entire body of work of the Master of Surrealism, making him forever the eternal substitute, the “double” destined to overcome the “first version conceived too much in the absolute”, as Dalí himself affirmed.

The identity of Salvador Dalí, the artist, was constructed upon the shade of his predecessor. The parents’ decision to bestow the same name upon the child born post-mortem was, for the artist, a gesture of devastating psychological intensity, feeding a sense of substitution that would haunt him for life.

This was not a simple homage, but a genuine “Dalinian dynastic question” that placed him as “a substitute of the first Salvador”, as noted by the art historian Joan Sureda.

The looming presence of the dead brother generated profound anxieties and obsessions in the young Salvador, marking his childhood and his art. The Master of Surrealism himself lucidly described the trauma.

In 1950, a psychoanalytical thesis on the “dioscuric myth of Dalí” by a friend, Dr. Pierre Rouméguère, struck the artist with the force of a revelation. Dalí recalled the moment as a violent shock:

“The question was settled on June 5, 1950, the day our mutual friend, Dr. Pierre Rouméguère read me his thesis on the dioscuric myth of Dali”, said Salvador Dalí, “For the first time in my life, amid incomparable thrills, I felt the absolute truth: a psy-choanalytical thesis revealed the sensational conflict at the basis of my tragic structure: the ineluctable presence, deep within me, of my dead brother, whom my parents had been so fond of that when I was born they gave me his name, Salvador. My shock at the doctor’s disclosure was as violent as at a revelation”.

This dynamic of co-existence and antagonism between the two Salvadors became a key for interpreting his art. The artist constantly felt himself measured against the idealised image of his brother.

“I managed to drop off to sleep only at the thought of my own death and by accepting the idea of lying at rest inside the coffin”, declared Salvador Dalí.

This obsession with the first Salvador justifies the artist’s fascination with decay and putrefaction, as seen in the images of rotting donkeys and the iconography reflecting his phobia of grasshoppers; and his continuous investigation into the processes of time and matter transformation, central themes in the sculptures of the Dalí Universe collection, exemplified by bronzes like the Dance of Time and the Persistence of Memory.

The inner struggle between the “first Salvador”, a terrestrial, idealised being, and the “second Salvador”, the genius and Master of Surrealism destined for immortality, was an incessant creative engine. Dalí did not merely submit to this conflict; he transformed it, sublimated it, and ultimately, exorcised it through his work.

Dalí himself provided one of the most penetrating definitions of this mystical, twin-like bond: “My brother and I resembled each other like two drops of water, but we had different reflections.” […] “He was probably a first version of myself but conceived too much in the absolute”, Dalí declared.

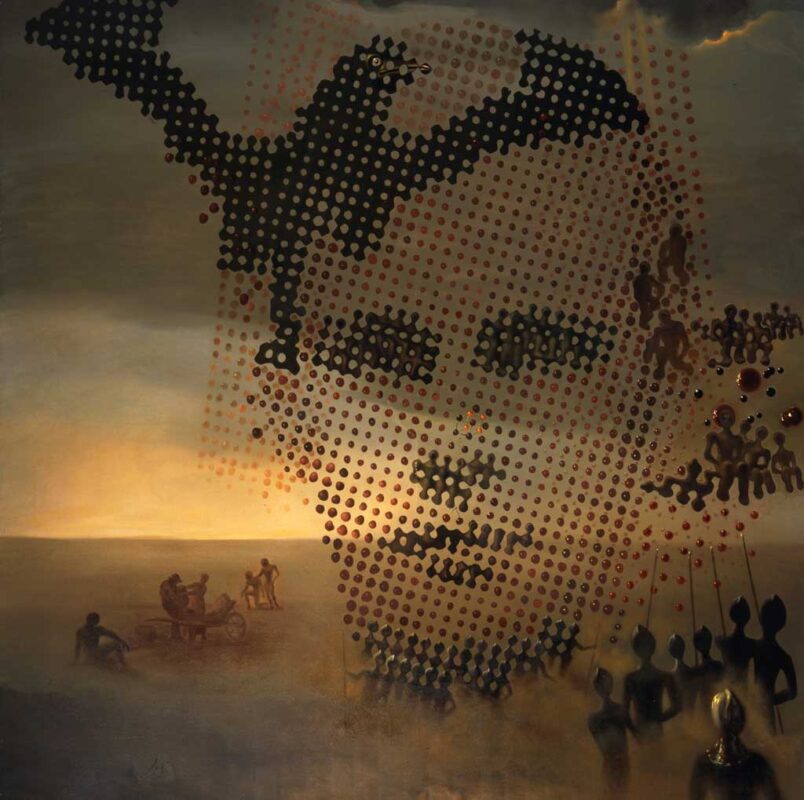

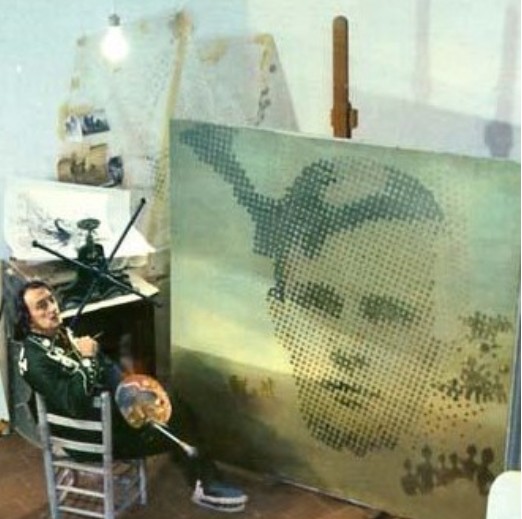

This duality was immortalised in one of his most iconic works, “Portrait of My Dead Brother” (1963). In this masterpiece, Dalí uses a striking pointillist technique, also echoing the aesthetics of Pop Art, to compose a single face: “The cherries represent the molecules, the dark cherries create the visage of my dead brother, the sun-lighted cherries create the image of Salvador living”, said Dalí.

.

Copyright/Fair Use

.

The portrait is not just a tribute, but an act of fusion and separation, in which the two Salvadors coexist and annihilate each other, united by a single molecule at the center of the nose, a symbol of the indissoluble bond and the struggle for identity. Dalí, with his unparalleled theatricality, asserted that he had to constantly assassinate the image of his brother: “Every day, I kill the image of my poor brother […] I assassinate him regularly, for the ‘Divine Dali’ cannot have anything in common with this former terrestrial being”.

The figure of the dead brother, far from being just a family memory, is a foundational element of his “Paranoiac-Critical Method”, a mechanism for accessing the subconscious and generating “irrational knowledge”. It is, in essence, the tragic foundation upon which the genius erected his entire existence.

On October 12th, the anniversary of the first Salvador’s birth, we do not merely celebrate a date, but the psychological crucible from which the unique, inimitable, and second Salvador Dalí emerged, the Master of Surrealism, who transformed his deepest trauma into one of the greatest artistic achievements of the 20th century.

.