“Sculpture is the best comment a painter can make about painting.”

Pablo Picasso

.

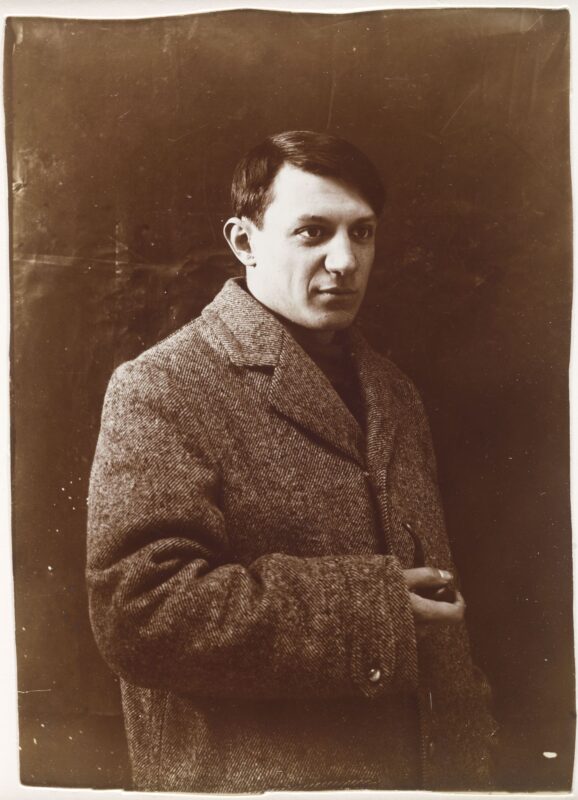

This week, the Dalí Universe celebrates the anniversary of the birth of Pablo Picasso, who was born on October 25, 1881, in Málaga, on Spain’s sun-drenched southern coast near Gibraltar.

Born to a painter and art professor, José Ruiz Blanco, and homemaker Dona Maria, Picasso’s creative destiny was ingrained in his Andalusian roots, destined to reshape the visual lexicon of the 20th century.

Salvador Dalí and Pablo Picasso stand, irrefutably, as two of the most significant and transformative forces in modern art. Their complex personal and profound artistic kinship is meticulously documented across the history of Surrealism.

When the young Dalí first travelled to Paris in 1926, his initial and most urgent desire was not to see the masterpieces of the Louvre, but to meet the celebrated Andalusian master himself.

In his legendary autobiography “The Secret Life Of Salvador Dalí”, the Catalan genius recounted that momentous first visit to Picasso’s studio, where the artist was preparing for his inaugural major solo exhibition.

Dalí, upon meeting Picasso, delivered a bold declaration that perfectly captured his mindset: “I have come to see you before visiting the Louvre.” To these words, Picasso, recognising the sheer audacity and devotion of the young man, is said to have replied: “You’re quite right”.

This meeting was the genesis of a connection that defined their careers, forging a rivalry imbued with mutual respect. As Dalí, with characteristic audacity, once proclaimed: “The two greatest disasters to hit Spain, after Philip II, were Picasso and myself.”

Beyond their contrasting temperaments, Picasso’s earthbound energy versus Dalí’s cosmic obsession, the two shared a fundamental mastery of form and a reverence for Classicism.

Dalí himself delved deeply into the mechanics of Cubism during the 1920s, a phase powerfully evidenced in works like his 1923 “Cubist Self-Portrait.”

This shared exploration of structure and dimension is especially apparent in their bronze work. Dalí’s sculpture, such as “Homage to Terpsichore”, exemplifies this blending of styles.

The twin dancing figures create a powerful, deconstructed composition, merging classical elegance with the abstract geometries of Cubist influence.

For both artists, sculpture provided the ultimate laboratory to test the limits of their painted visions. Their bronze creations seem to leap directly from the subconscious of their canvases, inhabiting a startling new dimension.

As Picasso himself once stated: “Sculpture is the best comment a painter can make about painting.”

Through their monumental and limited-edition sculptures, both Dalí and Picasso successfully constructed an enduring bridge between the flat plane of two-dimensionality and the immersive reality of the third, generating an “all-round emotion” that continues to captivate and challenge observers today.