“Wooden support derived from Cartesian philosophy. Generally used to serve as support for the tenderness of soft structures”.

Salvador Dalí

.

In Dalí’s work, the umbrella is a prime example of the Surrealist technique of challenging reality by reversing an object’s function or placing it in an unexpected, unsettling context. The very concept of the umbrella is paradoxical in its necessity: a functional form existing solely to counter a natural phenomenon.

This interrogation reached its peak in Dalí’s graphic works, such as the 1975-1976 lithograph “Anti-Umbrella with Atomized Liquid,” which is currently on display within the exhibition “1922 Comienzo: Salvador Dalí × The Bund City Hall” at the prestigious Bund City Hall, in Shanghai.

Part of Dalí’s visionary “Imaginations and Objects of the Future”, this work subverts its purpose entirely. The figure stands beneath an umbrella that, rather than shielding, appears to create rain, a literal reversal of logic that the Master of Surrealism used to explore his increasing interest in science, the atomic world, and the invisibility of matter.

.

.

As Dalí himself famously said: “As a surrealist painter myself, I never have the slightest idea what my picture means, I merely transcribe my thoughts, and try to make concrete the most exasperating and fugitive visions, fantasies, whatever is mysterious, incomprehensible, personal and rare, that may pass through my head”.

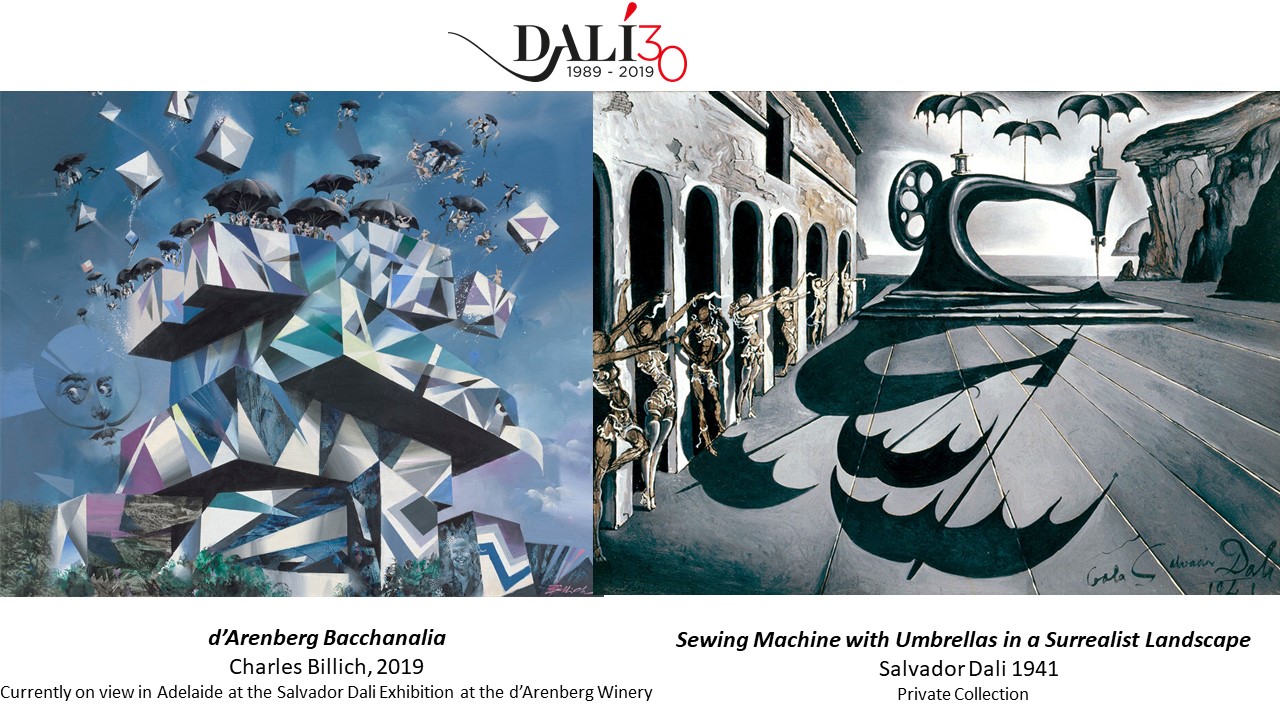

The umbrella also features prominently in other works of print and drawing, such as the “Sewing Machine with Umbrellas in a Surrealist Landscape” (1941), coupling the domestic and the natural with characteristic Surrealist chaos. The object became a key to unlocking the absurd in the everyday.

The umbrella’s most iconic and defiant appearance is captured in the legendary photograph of Dalí at the 1939 New York World’s Fair. The fair’s theme was “The World of Tomorrow”, a celebration of rational, sleek modernism. Dalí’s response was the deeply irrational and provocative “The Dream of Venus” Surrealist Pavilion. The famous image shows Dalí standing before the unfinished, “shapeless mountain” facade of the pavilion, holding an ordinary, black umbrella.

While the umbrella features primarily as an object of ready-made intervention and two-dimensional work, as seen in the 1970 engraving “Under the Umbrella Pine”, its conceptual role in Dalí’s oeuvre is monumental.

It represents the Master’s insistence on elevating the banal to the poetic, transforming a rain guard into a symbol of neurosis, contradiction, and the relentless downpour of the subconscious mind. The umbrella is a perfect encapsulation of Dalí’s mission: to destroy the “shackles limiting our vision” and celebrate the “violence and duration of your hardened dream”.

The image of the umbrella was not just a prop for Salvador Dalí, but a certified symbol that he formalised in the Surrealist lexicon.

Dalí included a definition for the umbrella in his entry for the “Short Dictionary of Surrealism” (1938), linking it directly to his complex philosophical framework and his iconic use of the crutch (or support). He defined the umbrella as: “Wooden support derived from Cartesian philosophy. Generally used to serve as support for the tenderness of soft structures.”

For Dalí, the umbrella’s handle serves as a rigid and rational support, holding up the soft, vulnerable, and imaginative material it is meant to protect. Just like the images of the lobster and the snail, the image of the umbrella also illustrates the pairing of the hard and the soft that Dalí loved.

In his autobiography, “The Secret Life of Salvador Dalí”,the Catalan artist openly declared his creative passion for the futuristic and provocative by listing his legendary “Symbolically Functioning Objects,” which he defined as a “total war against the functional logic of the bourgeois world”.

The Master of Surrealism announced his list of desired inventions, among which appeared the umbrella, described as an object of pure, eccentric pleasure: “An umbrella that squirts a mist of tanning moisturizer, perfect for bikini-clad girls at the beach at St. Tropez.”

The long list also included “A chair that comes up when one wishes to sit down,” “A motor which would run solely on the milk of a goat,” and “A cup of coffee with a detachable moustache” .This was not simply a list of fantasies but rather an aesthetic universe, where functional uselessness is elevated to beauty, and where the object ceases to serve reality in order to satisfy the sole, pure irrational desire.

The image of the umbrella continues to inspire artists, sculptors, and designers even today, who include this surreal object in their works and projects. A striking example is offered by the d’Arenberg Cube in Adelaide, which houses a selection from the Dalí Universe Collection inside.

.

.

The Cube’s extraordinary architecture, which already challenges the functional logic of traditional design, is crowned by a spectacular installation: 16 large umbrellas, 15 of which are black and one red, are installed on the building’s roof, which adds an artistic and surreal touch to the entire building, in addition to their function of providing shade.

Dalí would describe them as the “support derived from Cartesian philosophy” that must sustain the dream, a constant reminder that reality is mutable, and that the most banal object can be transformed into the most provocative symbol of the subconscious, celebrating the only true defense against the rain of rationality: the irrational.

.